To offset the weight of battery packs in electric vehicles (EVs), manufacturers are adopting multi-material strategies that integrate advanced high-strength steels, aluminum alloys, and carbon fiber-reinforced polymers (CFRP). This FAQ addresses the specific challenges this transition presents for assembly and how structural adhesives are emerging as an enabler for these complex systems.

Q: Why is the automotive industry moving towards multi-material structures?

A: The driving force is associated with a phenomenon known as mass decompounding. In an EV, the battery pack contributes significantly to the overall mass. Maintaining a heavy structure reduces the vehicle’s range, as it requires more energy to move and necessitates a larger battery. This leads to more weight, which calls for heavier brakes and suspension.

To break this cycle, engineers are employing a mixed materials strategy, as shown in Figure 1. The Cadillac CT6 and Chevrolet Malibu are examples of this method, which combines up to 13 different materials into one Body-In-White (BIW). One of the key aspects consists of a mix of 5xxx, 6xxx, and 7xxx series aluminum alloys for lightweighting, alongside dual-phase and martensitic steels for crash protection.

When it comes to the battery pack hierarchy, the housings must be stiff to protect sensitive lithium-ion cells from mechanical shock and random vibrations while remaining light enough to maximize range. This often involves bonding aluminum cooling plates to steel frames or polymer cell holders, resulting in numerous dissimilar interfaces.

Q: Why do traditional mechanical and thermal joining methods often fail in these applications?

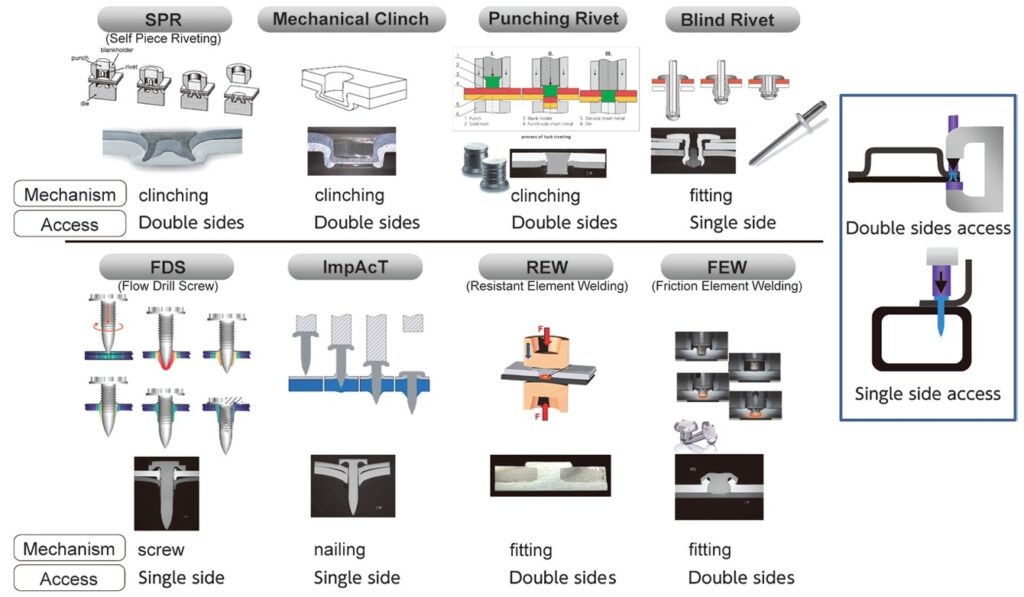

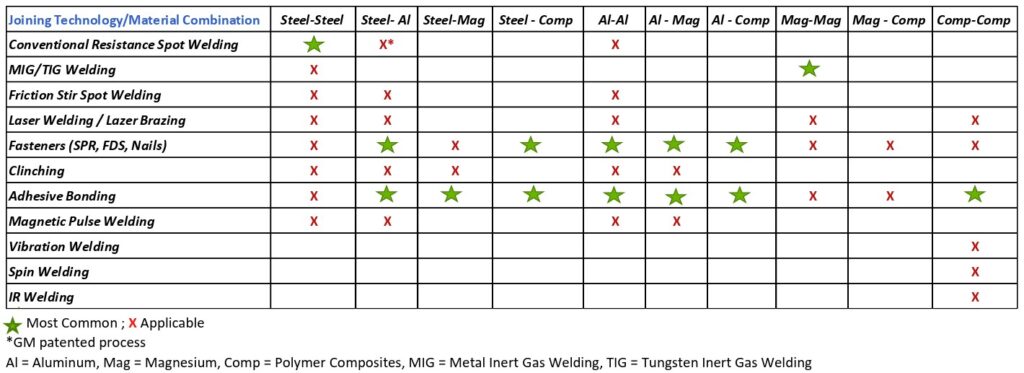

A: Traditional methods, such as resistance spot welding, were designed for steel-to-steel applications. However, when applied to the dissimilar materials found in modern EVs, they encounter physical limitations. Figure 2 shows a list of joining methods for dissimilar materials.

Fusion welding steel to aluminum or copper is difficult due to its low solid solubility. The process results in the formation of brittle intermetallic compounds (IMCs) at the interface. These IMC layers constitute weak points, serving as crack initiation points. Also, they increase electrical resistance, which is a failure point for high-voltage busbars.

Mechanical methods, such as Self-Pierce Riveting (SPR) or Flow Drill Screws (FDS), create point joints. Though mechanically robust, they lack a continuous seal. This deficiency allows for moisture ingress between the layers, which means a local battery effect can occur, accelerating galvanic corrosion.

Q: How do performance limitations and structural integrity issues manifest?

A: The limitations of mechanical joining become evident under the thermal and mechanical stresses normally associated with EV operation:

- Performance caps: In shear tests of aluminum-to-steel joints (Figure 3), the maximum load is often limited by the properties of the aluminum substrate itself rather than the joining element. As such, the surrounding aluminum deforms or tears. Hence, the structural integrity of the assembly is capped.

- CTE mismatch: The Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE) varies between materials. For example, aluminum expands roughly twice as much as steel. During the high-heat paint bake cycle (180-250°C) or even during driving, rigid mechanical joints cannot accommodate this relative displacement. This results in high internal compressive or tensile stresses that can distort the BIW or cause cracking in battery housings.

- Impact on busbars: For hybrid Al-Cu busbars, thermal fatigue from repeated charging cycles (which can reach 105°C) can loosen mechanical joints or crack brittle weld interfaces. Therefore, electrical impedance may increase, jeopardizing the power distribution network.

How do adhesives function as a structural solution?

Structural adhesives solve the issues of point loading and incompatibility. This phenomenon is illustrated in Figure 4.

Unlike fasteners, which concentrate stress at a single point (the drill hole), adhesives distribute loads evenly over the entire bonded surface area. In other words, their stress distribution eliminates stress risers. It allows for the use of thinner, lighter substrates without risking tear-out.

Modern adhesives additionally move beyond mechanical interlocking. They facilitate a transition to molecular or primary bonding, which refers to covalent and ionic interactions at the interface. This chemical bonding provides a connection at the molecular scale, making the bond durable under the hygrothermal conditions (heat + humidity) found in battery environments.

Adhesives are unique in their ability to bond virtually any material pair. As shown in the compatibility matrices in Figure 5, adhesive bonding is capable of joining the full spectrum of automotive materials, including the metal-to-composite (CFRP) interfaces that are becoming common in lightweight battery covers.

Adhesives are often used in hybrid joints, combining them with mechanical fasteners (weld-bonding or rivet-bonding). Ideally, this allows the adhesive to carry the shear loads and provide damping/sealing. On the other hand, the fastener ensures peel resistance and immediate handling strength during the cure cycle.

Summary

Joining dissimilar materials without an adhesive is just like bolting together two different pieces of clockwork that expand at different rates. The gears will eventually jam or snap due to the mismatch. Adhesive acts as a structural lubricant, insulator, and seal, allowing the different parts of the EV, such as steel, aluminum, copper, and composites, to move in thermal harmony while keeping the electrical current on its intended path, ensuring the system functions reliably.

References

Synergy of Steel and Satin: A Review of Metallic and Carbon Fiber Composite Materials in Modern Automotive Manufacturing, Convergent Materials Horizons

Adhesive bonding in automotive battery pack manufacturing and dismantling: a review, Discover Mechanical Engineering, Springer Nature

Towards Reliable Adhesive Bonding: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanisms, Defects, and Design Considerations, Materials, MDPI

Innovative and Highly Productive Joining Technologies for Multi-Material Lightweight Car Body Structures, Springer Nature

Current Research and Challenges in Innovative Technology of Joining Dissimilar Materials for Electric Vehicles, ResearchGate

Failure analysis of novel aluminum-copper joints for electric vehicle battery applications, Universidade do Porto

Multi-material Automotive Bodies and Dissimilar Joining Technology to Realize Multi-material, KOBELCO

Corrosion avoidance in lightweight materials for automotive applications, npj Materials Degradation

Mixed Material Joining – Advancements and Challenges, Center for Automotive Research

EE World related content

What is the best copper alloy for connectors in renewable energy and EVs?

Part II: What mechanical tests ensure EV battery safety and reliability?

Part I: What joining methods optimize EV battery production efficiency?

Why are adhesives important for EV thermal management?

how-fastener-designs-contribute-to-lightweighting-in-evs

How do EVs reduce noise, vibration, and harshness?